Matías Piñeiro on Reimagining the Rhythms of Shakespeare

Over the last five years, Argentine filmmaker Matías Piñeiro has established his own idiosyncratic approach to bringing Shakespeare’s comedies and their complex female characters into the present, crafting loose adaptations of As You Like It (Rosalinda), Twelfth Night (Viola), and Love’s Labour’s Lost (The Princess of France). His latest work, Hermia & Helena, takes on another comedy, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, following the romantic encounters and ambiguous relationships of a Buenos Aires theater director who is working on a new Spanish translation of the play while attending an artist residency in New York. Marking Piñeiro’s first time shooting a film outside his native country, Hermia & Helena unites a number of his frequent collaborators, including actors Agustina Muñoz and María Villar and cinematographer Fernando Lockett, with members of the New York independent film community such as Keith Poulson, Dustin Guy Defa, and Dan Sallitt.

Just before the New York Film Festival premiere of Hermia & Helena, Piñeiro stopped by the Criterion office to talk about the Bard, among other things.

When did you become interested in Shakespeare?

I first began appreciating Shakespeare as a reader, not as a theatergoer. I started reading translations by Latin American writers who had a new approach that focused more on making the text flow than on being scholarly. Their translations were written in contemporary Latin American Spanish, which made the plays feel less removed than those that had been done in European Spanish. This approach was very inviting, and I began to read Shakespeare more obsessively. I was very attracted to the comedies, and in them, I discovered these female characters I could relate to.

I was attracted by the contemporary element of the language in these translations and also by how they didn’t water down these very dense texts or downplay the obstacles presented by an earlier form of English. After reading them, I went back to the original English and tried to figure out how the syntax works, and I thought about how artificial and hard it is. Sometimes Shakespeare wants to give an example of something, and instead of giving two or three examples, he gives six. There’s something about the difficulty of putting that into a film that excites me. It challenges me to think of new forms.

How does Shakespeare’s syntax inform your approach to the films?

I think of cinema in terms of rhythm and equilibrium. Each film should have its own rhythm with regard to the elements that I choose to put inside it—I have to listen to how those elements move and relate to each other. I don’t like being melodramatic about stuff, and I try to avoid conventional storytelling. I want to honor the filmmakers I like by seeing the trajectory they have established for narrative filmmaking and trying to move it forward.

So you see Shakespeare as a jumping-off point and then you let the structure and actors dictate what the story will become?

The first thing I do is decide which play I want to tackle and which actors I want to work with. These are not adaptations, so I’m just grabbing a few elements. With this film, since A Midsummer Night’s Dream is the most famous comedy, I thought there was no need to include so much of it because everyone knows a little bit. I didn’t feel I had to explain it that much. In choosing to work with Shakespeare’s comedies, I’m trying to balance out how Shakespeare is usually approached, how people tend to focus on the tragedies and on the big men rather than the smaller female characters.

In Hermia & Helena, it’s not clear who’s Hermia and who’s Helena. If you’ve read the play, maybe you’ll enjoy the film a bit more, but I don’t need to have a distinction between what originates with the film and what originates with the play. They meet sometimes like two balls that hit each other and go their separate ways.

Throughout your films, you can feel the influence not just of cinema and literature but of painting too, particularly in the way you choose to photograph physical objects, which I find very beautiful. Their presence creates the sense that each character has accumulated a life.

Somehow I become very literal, focusing on this page or this postcard or this painting up close, so you can see the paint on the painting. I like how cinema captures what’s photogenic in objects. It’s a bit fetishistic—maybe I get that from Hitchcock—but I like how cinema can turn a free-floating element into an object, an image. I also like to be a bit anti-museum, in the sense that we are handling these objects. We don’t have to have a diploma to do a Shakespeare film. It’s life, it’s there—we’re eating while we’re rehearsing and we’re messing up the words, but we’re doing it and it’s alive.

Do you watch other Shakespeare films?

You have to. It’s impossible not to be interested in watching Michael Almereyda’s Hamlet or Laurence Olivier’s adaptations. At first, I was a little prejudiced, but I left that at home and went to see the movies and they were amazing. For me, Olivier’s Henry V is one of the best. It’s crazy what he does, and you learn a lot from him about how to shoot people talking. Then of course there’s Chimes at Midnight; all of Welles’s Shakespeare adaptations are important to me, because I like to see how he treated the text—he’s a butcher, he cuts a lot. But when you watch the films, you realize that the text is there for you to treat it in a way that is most suitable for you. You don’t exhaust the play; you’re just offering up another option, and the thing is there are innumerable options. Orson Welles helped me realize, okay, this can be mine somehow. Watching his movies was very liberating.

What are the first movies you ever loved?

Masculin féminin was very important to me. That was the first Godard that I watched, and it hit me in a way that I didn’t understand. At the time, I had more exposure to mainstream cinema. I remember enjoying L.A. Confidential, for instance. I don’t know if I was thinking about becoming a filmmaker then, but there was something in the experience of watching those images that touched me. Then there was also Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher, which I found both challenging and completely absorbing. Also, Bringing Up Baby. I think I’m referring here to extraordinary personal experiences at screenings. I saw Bringing Up Baby in Buenos Aires one summer as part of a Howard Hawks retrospective. Everybody was laughing so hard, and it was so much fun to be there—it was such a joyful experience.

That communal experience is so different from watching a movie alone.

That’s why I keep going to the cinema; that’s what I enjoy doing the most. One film that really marked me was Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman. I was trying to get ideas for a student short film and was told I had to see it, but this was in 2001 and it was not easy to do that. It was not until 2005, at a retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, that by chance I was able to see it. When I watched it, I realized that I had been influenced by it before I had even seen it. I had watched Akerman’s short films and read about Jeanne Dielman, and I had built this film in my head that had somehow influenced the short that I wanted to make. I think all of her work has influenced me as a filmmaker.

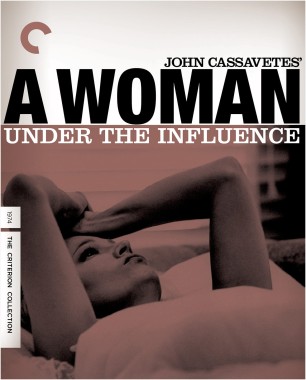

There are also films like A Day in the Country—it’s a film that I go back to all the time, and even now, when I see a shot of it, I cry. And Zéro de conduite. I also had a wonderful, very intense screening of A Woman Under the Influence at my place. I was feeling kind of melancholic, and that film made me cry so much—it was because of the film, of course, but also because of the experience of the screening, which hit me and left me with a scar. But a joyful scar, in a way.