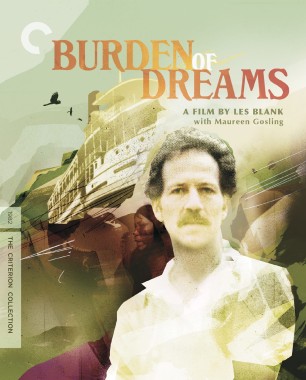

Burden of Dreams: In Dreams Begin Responsibilities

A shot of a street sign near the beginning of Always for Pleasure, Les Blank’s 1978 paean to New Orleans music, cooking, and dance, offers a telling contrast with the mood of Burden of Dreams, a project instigated the following year by Werner Herzog: “Joy St.” Metaphorically, this is the desired address for Blank’s body of nonfiction studies that show, as he puts it, “people full of passion for what they do.” Herzog, on the other hand, has consistently mined a territory on the far side of Sturm und Drang. “Joy St.” is not simply a foreign country on Herzog’s cinematic map; it is anathema to his goal of bleak existential adventure. Indeed, aside from their shared belief in passionate human endeavor—and a mutual affinity for marginalized folk cultures—the creative realms in which these two filmmakers operate could scarcely be more distant.

In 1980, Blank released a casually straightforward short with the self-explanatory title Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, the upshot of a silly bet Herzog made with Errol Morris. The German director’s invitation to document his South American production of Fitzcarraldo required a rather different, less transparent filmic approach, one that, perhaps inevitably, ended up registering the disparities in the directors’ aesthetic temperaments. Alongside its overt agenda, then, Burden of Dreams inscribes a fascinating double portrait in which Blank remains offscreen while still making his presence felt at every juncture. Adopting an ostensibly neutral recording style that cedes center stage to Herzog’s wildly excessive ego, Blank constructs a separate, reflective discourse able to comment on, reframe, and occasionally even subvert the proceedings he was assigned to record.

It’s easy to understand Blank’s initial enthusiasm for the project, despite any reservations he might have had about its potential unruliness: a free trip to an “exotic” setting (much of his work could be loosely classified as travelogue); an opportunity to examine an obscure Indigenous lifestyle; direct participation in the collision of old-world and new-world cultural values—a sporadic theme in his films. Likely less felicitous was Herzog’s identification with the historically derived, flamboyantly embellished figure of Fitzcarraldo, a white European devoting his considerable wealth obtained from the exploitative rubber trade to bringing operatic high culture to benighted natives. As several critics have noted, Herzog’s elaborate production scheme—involving arbitrary isolation of cast and crew far from Peru’s urban centers, the rigors of a harsh jungle climate, and reliance on a large contingent of Indigenous labor drawn from dangerously contentious tribal factions—recapitulated on a material level the dramatic arc of the fictional narrative. It is a story that, as is often the case with Herzog, veers toward alienation and madness, exuding an almost mystical admiration for the crazed adventurer.

Based on Blank’s previous encounters with ethnic American enclaves, which are marked by a combination of deep humility and appreciation, Herzog should have expected that he’d sympathize with the natives in any conflict involving even well-intentioned European interlopers. And it is possible that the risk-taking director selected Blank precisely because he knew the latter would be incapable of delivering a conventionally earnest puff piece. True to form, Blank renders an exactingly clear account of a massively chaotic shoot that, due to a host of weather- and tribal-induced delays, stretched over four years and necessitated radical changes in cast and scripted action. The documentary has a brisk chronological outline—augmented by informational voice-over narration—juxtaposing behind-the-scenes directorial glimpses, outtakes (including a weird scene on a church tower with original actors Jason Robards and Mick Jagger), direct on-camera interviews with Herzog, and passages of independent (i.e., non-Fitzcarraldo-related) observation.

Earlier in his career, Blank filmed promotional shorts for a poultry company and a cookie manufacturer; here the friction between that kind of disengaged professionalism and unmistakably subjective annotations helps infuse Burden of Dreams with a surprising density. According to Blank’s modest assessment, “If I did make a better film, it’s only because I had better subject matter.” Herzog’s disastrous spectacle proved a particularly ripe subject, yet it is Blank’s formal treatment, the evocative flourishes surrounding documented events, that helps define the meaning of his friend’s obsessive quest. For example, a brief prelude of aerial shots introduces a foggy Amazonian landscape over the sound of ethereal choral music; the pairing recalls openings of other Herzog films, yet it also bears a hint of Hitler’s famous descent from the clouds in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935), suggesting a theme of godlike domination that at once mirrors and diverges from Herzog’s fictional allegory. When production stalls, as it often does—Herzog claims his film is “cursed,” admitting that “the jungle is winning”—Blank filters in lively scenes of the local extras’ quotidian routines: food preparation, clothes washing, the blending of an alcoholic drink made from yuca plants. It is significant that most activities are “women’s work,” a realm that Herzog’s masculinist vision rarely acknowledges. Later, Blank constructs a touching vision of cross-cultural identification by juxtaposing the sound of a Caruso aria coming from a record player in an earlier shot with loving close-ups of native women, as if they are responding to the beauty of this alien voice. The moment recalls an archetypal collision staged by romantic adventurer Robert Flaherty in Nanook of the North (1922), when the titular Inuit marvels at a phonograph record (then jokingly decides to bite it). Unlike either Herzog or Flaherty, Blank clearly prefers the rhythms of collective effort, of sensuous community, over Eurocentric ideals of heroic individualism.

In essence, he has crafted a film about the interaction of premodern tribal existence with European modernity, epitomized by a movie narrative about the invidious clash of brute nature and a singular ego bent on his own, ultimately delusional, mission of cultural enlightenment. As Herzog’s project grinds on, he grows morbidly disenchanted. Seen in front of a variety of open-air backgrounds, he declaims to the camera: “I live my life, I end my life, with this project,” strangely insisting that Fitzcarraldo may be the last film to capture “authentic” Indigenous culture before it is overtaken by rampant homogenization, spearheaded of course by the onslaught of American commercialism. In sepulchral tones, Herzog denounces his filmic habitat: “The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery”; “It’s a land that God, if he exists, has created in anger.” Blank duly records the rants but remains skeptical. When Herzog speaks of the jungle as an “obscenity,” “the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder,” full of “fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and just rotting away,” Blank calmly cuts away to images of picturesque flora and fauna, a clear contradiction of Herzog’s nihilism.

Burden of Dreams has a climax roughly paralleling that of the fictional story. A large steamboat Herzog has purchased and shipped hundreds of miles to serve as his hero’s idée fixe—an object of strenuous (in fact, deadly) native labor—is cast adrift in a raging river during attempts to film a key scene involving Klaus Kinski. As the boat lurches, Herzog’s cameraman is thrown to the deck, sustaining bloody injuries. While cast and crew are placed in harm’s way, precisely the kind of existential test Herzog thinks will induce heightened drama, Blank and company hover in the wings, rendering the messy psychodrama with a clinical eye that nonetheless fosters our recognition of a proverbial ship of fools. As the crisis atmosphere ebbs, Blank gives himself the last word in a graceful coda featuring a village photographer’s black-and-white portraits of various members of the production team—plain but striking images rendered with a crude box camera. In this fond farewell, the documentarist implicitly chides the elaborate technological system imported to produce mere passing entertainment, against which the visual evidence of village life and its enveloping landscape are etched all the more sharply. Yes, it would seem that for Blank the jungle really has won.

In 1982, the making-of was not yet the standard practice it has become in mainstream cinema. Who knows what Herzog said to his backers to convince them of the necessity of dragging along a secondary film crew, but part of his personal rationale for the project must have been the prospect of exciting anthropological encounters in a remote land. The intrepid voyagers got more than they bargained for, and, arguably, it is Blank and company who took home the real cinematic prize. Herzog’s dream was in part predicated on an echo chamber of personal instability and failure—an uncanny defile of characters that starts with the historical figure, Carlos Fitzcarrald, on whom Herzog based his script and proceeds through the fictional Fitzcarraldo, the blatantly unhinged actor who plays him (Kinski), and the director at the helm of this wayward enterprise. Arguably, the buck stops with Blank, an agnostic with regard to the cult of “mad genius” underwriting Herzog’s metaphysics of creativity. In this sense, Burden of Dreams anticipates a strain of aberrant making-ofs that includes Fax Bahr, George Hickenlooper, and Eleanor Coppola’s Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991), a dissection of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now; American Movie (1999), Chris Smith’s beer-soaked diary of a no-budget slasher flick; and Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s recent Lost in La Mancha (2002), tracking Terry Gilliam’s doomed Quixote project. What remains unique in Blank’s precursor is an uneasy relationship between extreme artistic passion and an unvarnished beauty lurking just outside the frame.

This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2005 edition of Burden of Dreams.