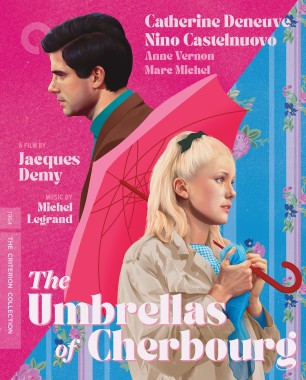

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg: A Finite Forever

Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg won what is now the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1964, launched a pop standard that has been covered by everyone from Frank Sinatra to Louis Armstrong, and made the twenty-year-old Catherine Deneuve an international sensation. It has been revived theatrically at least twice since its initial release, each time playing to new audiences and wider acclaim. With a CV like that, you wouldn’t think a movie would need defenders. And yet something about this film trips a wise-guy alarm in viewers who distrust musicals as a form, and who use “light entertainment” as a pejorative. The word that comes up repeatedly, in searches for the movie online, is curio.

The notion of Demy as the French New Wave’s twee miniaturist has long trailed his work. It hounded him in the years that bracketed the meteoric flourishing of the nouvelle vague, when he was the guy who made a musical with Gene Kelly the same year that Jean-Luc Godard was dispatching revolutionaries to incinerate Emily Brontë, the classicism she embodied, and cinema itself. It clung to him in the waning years of his career, when self-styled sophisticates could look at a movie as politically seething and formally daring as his 1982 musical melodrama Une chambre en ville and write it off as, sigh, yet another tunefest from poor outmoded Demy.

By the mid-1970s, the received wisdom on Demy was that he was a dabbler in irrelevant genres whose time had passed. And none of his films sounded sillier in the abstract than The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, this oddity in which every line of dialogue is not only sung but sung in French. It didn’t help that his movies grew harder to find in subsequent years, or that the superlatives of his style—brilliant color, exquisite framing, elegantly choreographed camera work—were grotesquely ill served by the aesthetic abattoir of lop-and-chop VHS.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that I saw Umbrellas for the first time, under near-perfect conditions—in a restored print at San Francisco’s glorious Castro Theatre, with an audience so besotted that they anticipated the melodies. I expected a mawkish pastiche—the judgment rendered in 1964 by the New York Times’ reliably fusty Bosley Crowther, who dismissed the film as “a cinematic confection so shiny and sleek and sugar-sweet—so studiously sentimental—it comes suspiciously close to a spoof.”

What Demy delivers instead is the most affecting of movie musicals, and perhaps the fullest expression of a career-long fascination with the entwining of real life, chance, and the bewitching artifice of cinematic illusion. More than any other film I know, Umbrellas affects people differently at different stages of life. When I first saw it, newly married but still remembering vividly the pangs of adolescent crushes, it played as tragedy: the story of a young love snuffed out by war, fate, and economic hardship. Over the years, seen in the light of Demy’s other films, it has come to seem more properly an exaltation of life’s bittersweet balances and trade-offs—of unexpected triumphs made richer by the dashed hopes that offset them.

When Demy released his masterpiece in 1964, the big-budget Hollywood musical was a mammoth cakewalking on a cliff’s edge. The musical as breezy, high-spirited entertainment had yielded to ponderous road-show events such as My Fair Lady and The Sound of Music; their success would beget extravagant decade-closing flops like Star! and Doctor Dolittle. On a genre noted for its lightness, prestige worked like carbon monoxide. The more these movies lusted for acclaim and recognition, the more stale, square, and ludicrous musical conventions looked.

But in Umbrellas, Demy found an ingenious way to extend the form of the screen musical, restoring its effervescence in part by reducing its scale to something recognizably human. Rather than surge and lunge in elephantine production numbers, the entire movie would flow on an uninterrupted current of music. The singing and color would evoke the piercing immediacy of first love, even as the abstraction granted a very contemporary distancing effect.

Is there a genre that demands a greater leap of imagination from a viewer, a more sophisticated acceptance of blatant artifice, than the movie musical? Someone watching, say, Vincente Minnelli’s Meet Me in St. Louis in essence enters into a compact with the filmmaker: I accept that characters will erupt into song and dance as naturally as conversation, and in return I will become their confidant, privy to their otherwise inexpressible longings. Accept those terms and a different emotional plane appears in the midst of Minnelli’s boisterous, crowded household—a private space in which the characters open their throats, their hearts, directly to us. This is not the real world; this is a world with the veil of realism parted, allowing the passions beneath to peek through.

This is life as viewed through Demy’s lens. But if Umbrellas uses the conventions of the Hollywood musical to express the immediate exhilaration of young love, it also subverts them to convey what’s left when the illusions fade. Among other things—many things—the film is about how our lives measure up against the romantic ideals we see on the big screen. “People only die of love in movies,” a character tartly observes—yet her pronouncement has an unmistakable note of regret.

Even before the title appears, Demy establishes a universe that fuses the commonplace and the cinematically heightened. The iris that closed on the black-and-white world of his 1961 debut Lola opens on the sepia-toned harbor of coastal Cherbourg, its workaday fleets of trawlers and naval ships. Without cutting—a seamless transition into the realm of stylization—Jean Rabier’s camera tilts directly down on the waterfront’s stone streets. A light rain begins; pastel umbrellas seen from overhead engage in delicate spatial choreography with the credits. On the soundtrack, we hear the first wistful iteration of Michel Legrand’s “Je ne pourrai jamais vivre sans toi,” the theme song that will follow the leads like the fading scent of prom gardenias.

In the first section, “The Departure,” set in November 1957, handsome, brooding Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) waits to get off from his job at the garage so he can see his girl. It’s not just any garage: as Demy’s widow, Agnès Varda, points out in her loving tribute Jacquot de Nantes (released a year after his death in 1990), it’s very much like the one Demy’s mechanic father ran. And it’s not just any girl: Deneuve is a vision of pristine loveliness. As Geneviève, the daughter of a single-mom shopkeeper, she’s introduced here as the most desirable element in a store window filled with the titular parapluies. She and Guy cavort down thoroughfares hot with neon yellows and sultry blues, as if the intensity of their passion has caused the town to bloom.

Her mother (Anne Vernon) tries to tell her to consider her future, to think of Guy’s callowness and the grim economic realities. (Another thing that changes over the years, as we watch the movie, is our grudging awareness that she speaks the truth.) She’d rather Geneviève cultivate a visiting jeweler (Marc Michel, in one of the earliest of Demy’s intertextual movie references, portraying the same dejected-suitor character who pursued Anouk Aimée’s dime-a-dance siren through Lola). Then comes word that Guy has been drafted for military service in the Algerian War. With only a night left together, Geneviève vows that she cannot live without him, and she offers up the same proof as the Shirelles in “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?”

At this point, the dizzying height of their infatuation, Demy cuts from the young lovers’ tearful exchange to the two literally floating down the slickened street in an embrace, carried by the swelling current of their ever-ready theme song. I have yet to see the movie with an audience that didn’t burst out laughing at the audacity of Demy’s artifice, the boldest such moment in the movie. It may take a second viewing to realize that the director isn’t just kidding their abandon but inviting us to remember the delirium of our own first loves.

They part in the time-honored fashion of movie lovers, with a railway-station farewell, but one that carries a whiff less of irony than of the drab everyday concerns that lie ahead. Then the next section—“The Absence”—begins, and the director starts to strip away the romance. Just as maman predicted, Guy’s letters come less and less frequently. Worse, Geneviève is pregnant, the shop is failing, and economic necessity demands that she find a provider. (The movie’s frankness about money as an overriding concern of marriage for women startles with each viewing; the topic helps Demy pass the Bechdel test with flying colors.) “I would have died for him,” Geneviève confides, despondent and confused. “So why aren’t I dead?”

There waiting, however, is Michel’s suitor, Roland. In a remarkable sequence, he is brought to Geneviève in a showroom of bridal dresses, where she, too, stands on display. A dissolve transports her veiled face to the altar, making her transition from mannequin to trophy complete. And yet what’s most striking is that Demy, the generous humanist, sees no reason to demonize Geneviève for her choice, nor to make Roland an ogre.

In the final section, “The Return,” a scarred, disillusioned Guy comes home to a Cherbourg leached of color. The swooning, string-laden arrangement of Legrand’s supple theme yields to louche marimbas and a down-at-heel cabaret ambience, as the wounded veteran limps past the haunts of a youth that now seems distant. He takes solace in booze and one of the cinema’s least judgmental transactions with a prostitute, before an unexpected rescuer snaps him out of his misery: his dying aunt’s caretaker, Madeleine (Ellen Farner), who represents a path to happiness that the movie hadn’t even led us to consider.

The coda that follows, set four years later, in 1963, takes place at an Esso station at Christmastime. (In Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 La Chinoise, Esso’s “Put a tiger in your tank” slogan would signify a cultural napalming by Western capitalism; for Demy, the gas station simply represents all the dully ordinary locales that prove to be the mysterious agents of our satisfaction.) Here, two young lovers who once vowed to wait for each other meet again a lifetime later, sadder and wiser. They now know the meaning of forever. The absence of the earlier color is stark. Their chance encounter is underscored by a hushed, mournful treatment of the Legrand theme—a dirge for a dream. As Geneviève drives away, Madeleine returns to the station with the couple’s young son—and at this point, Legrand’s score rises to an unprecedented crescendo. As in James Joyce’s “The Dead,” the snow that blankets the station falls on the death of a romantic idyll as well as the lives and loves that survive.

Is this the saddest happy ending in all of movies, or the happiest sad ending? The beauty, and profundity, of Demy’s vision is that it’s both. In Umbrellas’ opening scenes, it seems that Demy is whittling the Hollywood musical’s subject matter down to the particulars of daily life. But in this closing sequence, the converse is just as true: the movie urges us to see the color, hear the music in the currents of life and the rhythms of everyday speech. How different Demy’s sympathetic stylization is from that of a fascinating experiment like Herbert Ross and Dennis Potter’s lip-synched 1981 antimusical Pennies from Heaven, which considers its characters rubes for buying the tinny platitudes issuing from their mouths. Demy knows the limits of tuneful homilies, but he also understands why they lodge in our imaginations. They lodge in his too.

Demy would return to the musical throughout his career, starting with The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), whose public-space-as-playground resourcefulness suggests Jacques Tati’s PlayTime as staged by Arthur Freed’s MGM production unit. It’s a beautiful film, but its airy expanses were eclipsed in the year of Bonnie and Clyde and Weekend. By the time of Une chambre en ville, a shocking recitative musical that makes explicit the violence that’s always threatened or implied under Demy’s pastel surfaces, the sailors of his earlier films had given way to union-busting storm troopers, and infatuation had curdled into murderous obsession. (Perhaps alone among directors, Demy might have made something more than kitsch from a movie-musical Les misérables.)

None of these films have ever approached the popularity of Umbrellas, whose influence turns up in the least expected of places. Even if they hadn’t featured the undimmed presence of Deneuve, such dramatic musicals as Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark (2000) and François Ozon’s 8 Women (2002) would be unmistakable as tributaries of Demy’s initial vision. Curiously enough, one of the strangest yet most astute homages to the movie is a 2002 episode of the animated science-fiction sitcom Futurama in which the cryogenically thawed hero debates whether to clone a DNA sample from his dog, left a millennium earlier with the instruction not to move from his spot. He ultimately decides that the dog must have moved on and leaves the matter be—at which point the show cues a time-lapse montage of the dog waiting faithfully for his owner for years, until the moment he slumps to the sidewalk. The music playing over the montage is Connie Francis’s recording of “I Will Wait for You” (the Americanized version of Legrand’s song)—that anthem of a finite forever and an eternally preserved present that never loses its ache.

“One of the sad things about our times, I think, is that so many people find a romantic movie like that frivolous and negligible,” Pauline Kael lamented about The Umbrellas of Cherbourg in a 2000 interview. “They don’t see the beauty in it, but it’s a lovely film—original and fine.” And it’s just as lovely today—its color just as vivid, its hopes just as fragile and delicately suspended. When I watch it now, it reminds me of the doorjamb in my grandmother’s house with my height marked in pencil over the years, or the dresser with my own children’s measurements notched along the edge. In it I see the person I was and the person I turned out to be, but the object itself will always be the same. It will wait, forever.

Special thanks to Scott Manzler, Sarah Finklea, Alicia, Kat, and Jamie. This piece was originally published in the Criterion Collection’s 2014 edition of The Essential Jacques Demy.