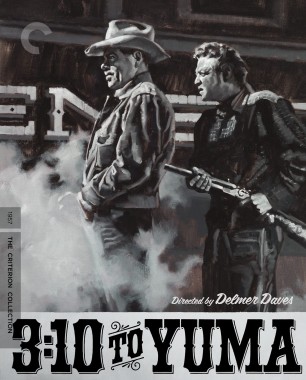

3:10 to Yuma: Curious Distances

Many of Delmer Daves’s films are beloved today, but to say that he remains a misunderstood and insufficiently appreciated figure in the history of American movies is a rank understatement. Daves was at once a true artist, a western specialist, and a Hollywood pro whose work was respected by insiders but received little in the way of official recognition. Unlike, say, Howard Hawks or Nicholas Ray or Anthony Mann, directors whose careers afford rough parallels to that of Daves, he was not reclaimed by auteurism, the strain of film criticism that originated in France as the politique des auteurs and flowered here in the United States as the “auteur theory.” In fact, Daves could be counted as one of its casualties.

In the grand reconsiderations of our national cinema that were written between the 1950s and 1970s, Daves was tagged as a nature lover, a Hollywood naif, a purveyor of the conventional. In large part, this was because he simply did not fit the auteurist mold of the subversive maverick injecting notes of unease, distress, and irrationality into otherwise conformist narratives, under the eyes of nervous studio heads and watchful censors. He was drawn to the bonds between people rather than the divisions, to friendship and love rather than discord and vengeance. He was very good at dramatizing destructive urges and behaviors, embodied by secondary characters who shadow the paths of his honorable protagonists, and no filmmaker had a richer feeling for the aching loneliness of western life. Nonetheless, there is a consistent and coherent sense throughout Daves’s films of the world as essentially and innately benevolent; he was one of the only American filmmakers outside of the avant-garde to work with a genuinely transcendentalist spirit and outlook, no matter that it was filtered through the commercial demands of Hollywood moviemaking. This places his perspective as far from the glad-handing optimism of truly conformist filmmaking as darker sensibilities like those of Ray, Mann, or Hawks.

A comparison between Daves and Hawks is particularly illuminating. Daves was a filmmaker of grand rhetorical gestures; Hawks was not. Daves was passionately interested in landscape and history, Hawks in neither. Daves was a fundamentally openhearted artist of the natural world; Hawks’s sensibility was sleek, sophisticated, and urban, whatever the setting. It’s interesting to consider their dissimilarities in light of the frequently repeated story that Hawks said he made Rio Bravo (1959) as a corrective to both Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952) and Daves’s 3:10 to Yuma (1957). Daves’s film, in many ways patterned after High Noon (ticking-clock western suspense within a compact time frame, a brooding and endlessly repeated theme song, stark black-and-white imagery), centers on a protagonist who is almost overcome by inner conflicts. For Hawks, such a hero was unthinkable. His best movies, including Rio Bravo, feature aristocratic circles of the confident and able, from which the self-doubting are barred. Even Dean Martin’s recovering-alcoholic deputy in that film is innately skilled—he just doesn’t think he is. For that reason, Hawks’s film, which also features a captured criminal whose friends are coming to get him, is not a suspense story at all but, as many have pointed out, a relaxed and endlessly digressive interval spent with a group of pals.

In auteurist lore, 3:10 to Yuma has always come out on the losing end of this comparison—Rio Bravo is bravely, idiosyncratically “pragmatic,” while the Daves film is merely, and fashionably, “psychological.” But that is to understand the matter only as Hawks did. He watched Daves’s film, recognized nothing but the antitheses of his own predilections, and reacted accordingly. But to see 3:10 to Yuma only as Hawks did is hardly to see it at all. It amounts to much more than a “psychological western,” and more even than a “suspense classic,” as it has been validated by official film culture. It is, as Bertrand Tavernier has written, a “magnificent parable of liberty”—as well as a moving depiction of a marriage at a crossroads, a fascinating study in ambiguity, and one of the most visually striking of all westerns. On many levels, 3:10 to Yuma stands alone in the genre and, I think, in American cinema.

An extremely terse 1953 Elmore Leonard story provided the basis for the film. A deputy sheriff brings a prisoner to a hotel room in Contention City, Arizona, where they remain until it’s time to walk through a gauntlet of the prisoner’s armed gang to the 3:10 train bound for the federal prison in Yuma. The question of why the deputy risks his life for the paltry sum of $150 a month goes unanswered. Leonard himself was initially disappointed that it did not remain so in the film version. This would have been a tall order: the mystery of the deputy’s motivation is made possible by the intense narrative compression of the story and would have been difficult to sustain throughout a feature-length running time. (In the intervening years, Leonard has reversed his opinion of the Daves film and now considers it one of the best adaptations of his writing, along with Budd Boetticher’s 1957 The Tall T.)

“Three-Ten to Yuma” was adapted by Halsted Welles, who had a long career in radio drama and television but died with only five film credits to his name, including Daves’s 1959 The Hanging Tree and Phil Karlson’s 1967 Civil War western A Time for Killing. Welles and Daves (who, having worked as a screenwriter before he began directing, always did a “director’s polish” on scripts for his pictures, even when he wasn’t credited with writing them) made some interesting choices based on the sparse information provided by Leonard, not only filling out the characters but actually deepening them. In the story, the prisoner complains that it’s going to rain and asks the deputy to close the window in the hotel room. In the film, the question of rain becomes a key dramatic element. There’s a drought, and the hero, now a rancher named Dan Evans, is desperate for cash, which is why he agrees to risk his life by guarding the prisoner, Ben Wade—it is also why Wade never stops attempting to bribe Evans with increasingly large sums. Thus, in the film, Wade asks Evans to open the window because it’s so hot outside. In the story, the deputy refers to his wife and children, but in the film, we come face-to-face with Evans’s family, and so does Wade. In the story, there is a flash of kinship between guard and prisoner, which is expanded and compellingly complicated in the film—giving rise to the enigma of Wade’s generosity at the final, crucial moment. Welles and Daves also made a fascinating and little-remarked change that renders the entire question of Wade’s moral character more complex. In the story, a member of the prisoner’s gang has shot and killed a stagecoach driver during a holdup. At the very beginning of the film, we witness that holdup, as do Evans and his sons. When the driver pulls a gun on the gang member who is taking the money from the strongbox, Wade shoots his own man (presumably reckoning that he’s a goner anyway), then the driver, and then gets back to business.

Daves originally offered the role of Evans to Glenn Ford, who chose instead to play Wade, supposedly because he had been advised as a young man by John Barrymore to never turn down the part of the villain. Daves responded with the equally unorthodox casting of Van Heflin as Evans. Heflin was an interesting actor, a soft and often genuinely unappealing presence who specialized in characters either gnawed by doubt and guilt or haunted by the specter of humiliation. Ford, on the other hand, radiates ease, confidence, and charisma as Wade. Not only does the casting up the ante of the cat-and-mouse, war-of-nerves exchanges between Wade and Evans, but it also immediately points the film in a more surprising direction.

Daves took a lean western tale and fashioned out of it a spiritual suspense story about a trio—a husband, a wife, and their improbable observer. The film plants seeds of doubt between Dan and his wife, Alice (Leora Dana)—he imagines that she is questioning his manhood and his ability to provide, and that she has been charmed by Wade. We in turn study Alice’s face for signs of apprehension and disquiet, and sense that she and Dan have been down this road before; we can see their exhaustion, that it is close to the edge of desperation. We can also see that Wade is visibly moved by Alice, and we wonder when and in what form this sentiment will manifest itself.

The core of 3:10 to Yuma is a marriage, not an idealized marriage but something like an actual one, with its wearinesses and projections of fear, its longings and its renewals. Heflin’s Evans is often mindlessly grouped with his beleaguered rancher in Shane (1953) or his man-with-a-dishonorable-past in Act of Violence (1948), but this is a different kind of character, a nuanced creation shuttling between fatigue, rattled stoicism, and bursts of nervous upset, and Heflin’s finest moments are his quietly barbed exchanges with Dana. She is on-screen for a relatively brief period, perhaps only a third of the movie, but her early moments with Heflin, and the scene in which she and her family share their dinner table with Ford, set the tone for the film. Her character amounts to much more than a mirror of her husband’s insecurities or his moral bedrock—these are genuine one-to-one transactions in which the shifting emotions passing across their open and visibly careworn faces have been as attentively cultivated and integrated into the texture of the images and the action as in a late Bergman movie.

And then there’s Wade, the privileged witness to this couple’s most intimate emotions. The term “morally ambiguous” has been employed a little too often over the past two decades, but it certainly fits this charming outlaw who shoots down two men, including one of his own, and doesn’t even stop for a breath; who is prone to romantic reveries and expressions of tenderness; who shifts in the blink of an eye from the affable to the mercenary and back again. Ford and Daves had already found a common wavelength in Jubal (1956), and they created something even more refined and surprising here with Wade, a remorseless murderer with a capacity for awe. Critic David Thomson has complained that the film suffers from Ford’s “inability to be nasty,” but that is pretty much the point: goodness and mercy often arrive unannounced in this film, and come as a surprise even to those who bestow them.

3:10 to Yuma is not just a penetrating character study but a vision anchored by Daves’s understanding, as a westerner himself, of life in the West, as well as his sharp graphic sense. He shot the film in Arizona in winter, in Elgin, Willcox, Texas Canyon, and Old Tucson—a movie studio built outside Tucson and used as a setting for many westerns—and farther north in Sedona. “On 3:10 to Yuma, the moment the sun rose and broke the horizon, I’d be aiming right at it,” he explained to writer Christopher Wicking in a 1969 interview. “We got beautiful long, long shadows. It’s not possible to get that effect in the summer.” Daves wanted deep, rich blacks in the images, to reflect his own memories of drought conditions in the region, an effect heightened by the unusual use of red filters (his cameraman, Charles “Buddy” Lawton Jr., had pursued similar high-contrast black-and-white imagery with Orson Welles in 1947’s The Lady from Shanghai), and he had to go to Columbia head Harry Cohn to make his case. The result is a western that looks like no other, the texture of its images alternately stark and lustrous, enhancing the loneliness of houses, animals, and human figures against the endlessly flat earth and wide-open skies.

This loneliness, felt inside and out, is the emotional cornerstone of the film. It is behind the lovely interlude in which Wade and Felicia Farr’s Contention City barmaid, Emmy, talk each other into bed for a stolen hour, and speak after the fact as if they were already each other’s distant memories. It is behind the curious distances between people, the sense of lives lived at a remove from those of others. And it informs the beauty and power of those remarkably expressive high-angle boom shots for which Daves became known, and which are a particular characteristic of this film’s signature.

Daves considered himself a pioneer of the boom, and he designed his own special rig. “Other booms always had to be on an angle,” he told Wicking, “but our boom goes straight up in the air like a telephone pole, and you can figuratively shoot all around.” Daves used the boom in many of his films for the “poetic image,” but in 3:10 to Yuma, it becomes a vitally important creative instrument—to paraphrase critic Fred Camper on Robert Mulligan, it allows Daves to emotionalize space. “I’m doing it by instinct half the time, slowly, slowly, but now soaring,” Daves explained. “If you do it that way, you do it according to feeling.” At one moment, the boom is akin to a silent benediction on the characters, carrying their hopes aloft; at another, it is used to underscore the force of a pack of riders cutting through limitless spaces; and in the final scene, the boom takes the camera soaring with Alice’s joy. It’s an appropriate ending for a film in which the spiritual education of the three principal characters is not a by-product or a subtext but at once its central motor, its force, and its final destination. By the time it reaches its end, Daves’s film has nowhere to go but up.

This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2013 edition of 3:10 to Yuma.