By Brakhage: The Act of Seeing . . .

Stan Brakhage’s films explode with sensual beauty: bursts of color heightened by extreme contrasts in hue and shape and by stunning depth effects; more monochromatic passages of nonetheless equal intensity that sensitize one to the glories of tiny differences; nearly flat, slowly changing fields of color that wave like blankets in the wind, only to be interrupted by a cut that opens up a vast space; rapid explosions of paint that seem just on the cusp of suggesting a nameable object. The viewer is taken through such complexities of experience that the effect is a little like having one’s eyes flushed out. But the work generally doesn’t aspire to what is often meant by purity; instead, it’s chock-full of the conflicting emotions and general messiness of life itself. The montage of Dog Star Man (1961–64), which juxtaposes its characters, principally Brakhage himself, with imagery of blood vessels and the sun, the forest and the stars, family and architecture, and explicitly erotic imagery, evokes numerous associations, from the banal to the sublime. Layers of faces and rocks and paint on film combine in multiple superimpositions, ultimately building to a meditation on one man’s place in the cosmos that can also be read, apart from its hint of a plot, as a light-poem.

Though his status as the most important and influential of avant-garde filmmakers is secure, many still seek to justify Brakhage’s significance by pointing to the degree to which his stylistic innovations have influenced mainstream movies (the credits of Seven being one recent example), as well as television commercials. This formulation is more than a little ironic, because his fifty years of filmmaking, comprising nearly four hundred films, ranging in length from nine seconds to over four hours, provide a passionate opposition to the ethos of both conventional dramatic narrative films and most documentaries—offering alternatives in the ways in which they were made, in how they should be viewed, and in what they’re all about.

A conventional narrative film is a machine for the manufacturing of emotions: some characters and scenes evoke empathy and others create tension and fear. These emotions are provoked primarily by the subject matter—an image of a marauding ax murderer would scare anyone—and, only in the very best of narrative films, also by the style. But while subject matter is important in Brakhage’s films, they do their work mainly through composition, camera movement, rhythms within images, and the rhythms of editing or paint on film—they’re best seen, in other words, as light moving in time. A documentary is typically of interest because of its subject matter, proceeding as a kind of show-and-tell, with talking heads or an omniscient narrator conveying information. Brakhage’s films have few or no objective facts, existing primarily in a kind of virtual space within the viewer’s imagination, and in the subjective interaction between viewer and film.

Brakhage wants to “make you see,” a D. W. Griffith line he often cited, but with a crucial difference: his films eschew the manipulations of mainstream narrative and instead invite you to a variety of kinds of seeing.

If the model for making the Hollywood film was Henry Ford’s assembly line, with each phase of the production being handled by a different individual or group, Brakhage, like most avant-garde filmmakers, worked almost completely alone. He occasionally made films with actors, and even used a small crew; some of his films are collaborations with individual workers at film labs—or with other filmmakers. But his central model is the loner with a camera, filming the world and then editing alone, or the loner scratching and painting directly onto the filmstrip. Most of his films were made on minuscule budgets, tens or hundreds of dollars rather than tens or hundreds of millions, which allowed him, though not without considerable difficulty, to finance them himself, free of any interference.

One key aspect of avant-garde film, present perhaps most strongly in the work of Brakhage but found also in that of such predecessors of his as Maya Deren and Gregory J. Markopoulos, and of such successors as Ernie Gehr and Hollis Frampton—and even of later filmmakers who weren’t heavily influenced by Brakhage, such as Lewis Klahr and Su Friedrich—is the kind of relationship it establishes with the viewer. Like much modern art, and unlike mass-market entertainment, it addresses the viewer as an individual rather than as a member of a group. To watch a Brakhage film is to be profoundly alone: alone with oneself, alone in the process of discovering new things about oneself. Indeed, Brakhage often said that he preferred that his films be seen in the home; and in the sixties and seventies, he made a number of 8 mm films, whose purchase was affordable.

Thus it’s especially important not to view Brakhage films in the way most are accustomed to screening videos. I would suggest trying to approximate the conditions of a cinema as much as possible. Because of the complexity and subtlety of Brakhage’s films, they prove most rewarding on multiple viewings. Those new to his work may be better off choosing a few to see at a time rather than trying to watch these discs straight through. Also, the room should be completely dark. One should sit fairly close to, and perhaps at eye level with or even lower than, the screen. The projected film image has, in its clarity and colors and light, a kind of iconic power that is key to Brakhage’s work, and it’s important to try to see whatever monitor one is viewing these films on in a similar way. Brakhage made most of his films silent because the rhythms of almost any soundtrack tend to dominate the rhythms within an image, and visual rhythms are crucial to his work. Thus the interruptions of chatting, people coming into and leaving the room, the phone ringing, and so on can prove almost completely destructive to these films’ subtle delicacies.

Most importantly, the viewer of a Brakhage film must learn both attentiveness and openness. I’ve long guessed that when most people start to watch a movie, expecting a relaxing encounter, images that will tell them what to see and think, and a story that “sucks you in,” their speed of perception slows down. This won’t work at all for a Brakhage film. The viewer needs to be relaxed, of course, but ready to receive varieties of images and rhythms, and able to see fast—in the 1960s, a generation of viewers not yet trained by the rapid cutting of later TV commercials and music videos used to complain about headaches from Brakhage films because of their speed. But even in the apparently slower sections, every jiggle of the camera is important. Most of all, the viewer’s role needs to be reimagined: from a passive receiver to one who meets the film halfway, actively plumbing the depths of its imagery and the various themes and ideas suggested by its subject matter—imaginatively dancing with its flickering rhythms.

Ideally, these films should also be seen on film, because the quality of projected film light is completely different from the light of a video monitor. For one thing, a projected film has a more chiseled, absolute quality, despite its flicker, because the flicker is caused by the projector shutter opening and closing many times a second, so that what one actually sees is a succession of still images. Video light, by contrast, is constantly moving. The great advantage of DVD is its availability for home viewings, and especially for multiple viewings, but it should never be taken as a substitute for viewing the films on celluloid, and it is my hope that more screenings, rather than fewer, will be the result of this project.

Brakhage said of reading Freud, “The first thing I understood is that here was a man trying to save his own life.” Brakhage later acknowledged that the quote applied to him as well: his films are made with an intensity, a kind of “wit’s end” desperation, that suggests a consciousness on the brink. Brakhage was not only a craftsman doing something he loved; he used his craft to try to come to an understanding of whether—and on what terms—he could go on living. This is true in the lurching, intense movements used to shoot an adolescent party in his third work, Desistfilm (1954), where the camera mimics drunkenness; in the epic mixture of triumphantly poetic montage and abject failure that haunts Dog Star Man; in the terrifying suggestion of death in the central strip of darkness at the beginning of The Dark Tower (1999). While the at-the-edge quality of his work may have been born out of his personal psychology, it ultimately becomes, particularly in his major films, a philosophical inquiry into the nature of existence.

There is no solidity in Brakhage’s work, no fixity, no predictability, no symmetry—and really, if one or more of those things is present, one can be almost certain that it’s present as an intended horror, a vision of dread, as in the mirror-image symmetries in Delicacies of Molten Horror Synapse (1990). His work was made in opposition to, even in terror of, the notion of the static, the fixed, the given. Objective measurement, predetermined forms, the overall arc structure of most narratives—all were to be undermined because they block the individual from experiencing the unpredictability of the inner life.

Many of the techniques Brakhage developed or refined—the use of the handheld camera to express his subjective reactions to what is being filmed, his very physiology realized through its tiny jitters; the physical insertion of tiny images into the filmstrip in Dog Star Man; or the application of scratches and paint directly onto the film surface to approximate closed-eye vision (lower your eyelids to see what he means)—can be seen as part of a larger exploration of human subjectivity in all its varieties. He answers the idea that photography is an impersonal recorder of “reality” with the notion that reality itself is inseparable from human consciousness, and that “shared” seeing—the type of eyesight that allows one to walk across a room without bumping into things—is no more valid, and is aesthetically less interesting, than the play of light on objects, the movements of dust particles in the air, or personal mental images. The immateriality of his films’ light becomes a metaphor for the shifting nature of thought itself.

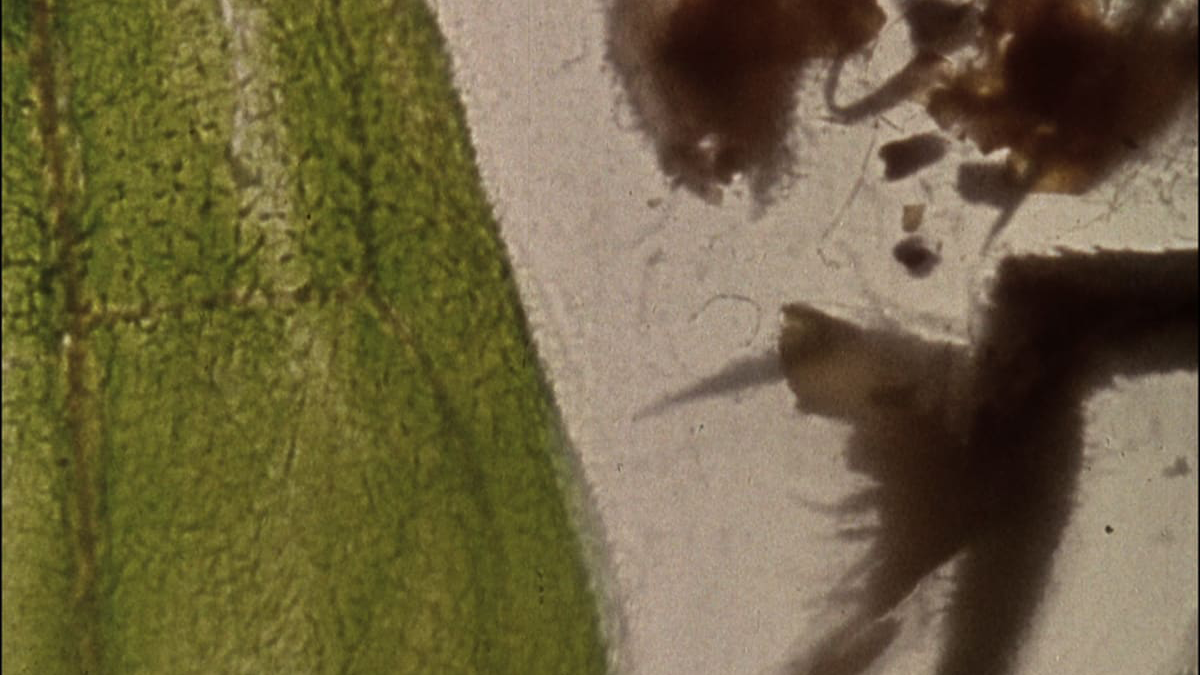

The variety of images and techniques in Brakhage’s films is partly about giving form to his eyesight, and in that sense, he can be called a documentarian of subjectivity. But a key effect of his work is to sensitize each viewer to his own subjectivity. One can’t completely figure out the provocative but mysterious interaction between the four figures in Cat’s Cradle (1959), but kept on edge by the very rapid intercutting, the viewer is at once encouraged to come up with his own interpretations and prevented from settling on any one idea. The viewer who struggles through the autopsies Brakhage films in The Act of Seeing with one’s own eyes (1971) will soon discover that the film is also a curious, admittedly creepy, study of the varieties of light reflected off of skin, with luminous fluid appearing to dance with the camera. Lovers of Brakhage’s work have found, in fact, that it can constitute a kind of eye training, a way of helping one see the world more imaginatively in a variety of situations, ranging from moments of intense emotional crisis (his early Anticipation of the Night [1958] contemplates suicide) to moments of boredom (sitting in an airport is the subject of Song 12 [1965]).

Despite their apparently private nature, Brakhage’s films also have a social dimension, arguing against, and offering an alternative to, the object fetishism that dominates our culture today. To the ethos of the television commercial (of which he made a few, decades ago, though with no great enthusiasm), in which a series of images leads up to a picture of the product, reducing beautiful women or pastoral scenes to an automobile or a beer can, Brakhage offers the opposite: objects being transformed into moving light. Using changes in perspective and focus (including extremely soft focus), changes in exposure (Brakhage argued that there is no such thing as “correct” exposure, that light and dark images are as valid as “correct” ones), paint on film, and other devices, he redirects attention away from objects and possessiveness and toward a state of nonacquisitive, almost immaterial flow.

Omnivorous in his acknowledged influences—which ranged from Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein to J. S. Bach and Olivier Messiaen to modern choreographers Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham; from J. M. W. Turner and Jackson Pollock to Chinese ideograms and much, much else—Brakhage made no pretense to academic objectivity, instead finding elements in each that inspired him, that he could make his own. Perhaps the vast range of his influences partly accounts for the diversity of his work, from the almost documentary Window Water Baby Moving (1959) to the collage film Mothlight (1963) to the epic narrative Dog Star Man to films in which he hand-paints over photographic imagery, such as The Dante Quartet (1987), to completely “abstract” hand-painted films, such as Lovesong (2001). But his project was always to explore the richness of seeing, and of life in its totality, accepting no givens about what seeing or the film image or life itself is but always pushing toward the unknown.

Brakhage’s work frequently proceeds by setting up contradictions on a variety of levels. In many of the later hand-painted films, one opposition results from the fact that most individual images are repeated for between two and four frames, producing images that last from one-twelfth to one-sixth of a second. The speed is fast enough to suggest movement but slow enough to permit each painting to be seen as an individual still, creating an exquisite tension between the two parts of cinema’s dual nature.

While Brakhage’s films are replete with other oppositions, on the levels of both style and subject matter, his editing is not merely—or even mostly—oppositional. Most frequently, a sequence will be followed by a kind of lateral move; rather than answering one set of visual forms with its opposite, he understood that opposition is a form of affirmation, because it accepts the terms of what is being opposed, and instead sought to shift the very grammar of the film’s discourse. For most of the brief two minutes of Black Ice (1994), we see superimpositions of abstract patches of color that seem to be zooming toward us with other fragments that are moving in different ways. The zoom effect is itself a perfectly balanced contradiction: shapes are rushing toward the eye, but it also feels as if one is falling into a void. (The film, in fact, was inspired by a fall Brakhage took on a patch of black ice.) Then, suddenly, at the end, the image flares to white with a hint of color, goes to solid black, and finally fades again to almost solid white. This “surprise” ending, a suitable conclusion to a fall, nonetheless feels very different from everything that has come before it, redefining the film’s terms.

Brakhage was a master of filming human subjectivity, but every moment that appears to valorize the affections, the moods, is balanced by a sense that the work itself is in danger of coming apart, that its beauty and unity are fragile, that its making acknowledges its own destruction. And just as his films’ self-referentiality can be defended on a strictly factual basis, as an acknowledgment of what they materially are, so can this larger theme: in the world, too, no object is permanent, and these assemblies of vibrating particles will eventually crumble into dust. Even the cathedrals that seem so solid today will not survive forever, and so the brevity of Brakhage’s hand-painted evocation of stained-glass windows in Untitled (For Marilyn) (1992), spectacular fragments of color that coalesce for a few moments into a miraculous sense of wholeness, ultimately reflects, almost in the manner of a vanitas painting, on the impermanence of all things. At the same time, meaning in Brakhage’s films is itself fragile: while at every moment one can envision multiple interpretations, one also, in part because of the constant metamorphosing of his forms, glimpses a void in which the whole possibility of meaning vanishes.

The white at the end of Black Ice has analogues throughout Brakhage’s work, and in his film-to-film evolution as well. Sensually beautiful but fragile, containing records of their own incompleteness, always haunted by a contemplation of death, these films are true to the complexities of life while also expanding its possibilities. Proceeding from an awareness of our tendency to limit ourselves by settling on a single way of thinking, a single way of seeing, a single set of objects desired or possessed, Brakhage’s art denies the whole skein of bourgeois complacencies inherent in possessiveness, in the notion that who we are depends on what we own or what “personality” we project. Brakhage offers this alternative: that each of us can become an inner explorer, continually pushing toward some new frontier of consciousness.