Paths of Glory: “We Have Met the Enemy . . .”

In 1945, a teenage Stanley Kubrick was given a job as staff photographer at Look magazine, where he published more than nine hundred striking images, most of them in the realist style of New York School street photography. By the end of the decade, he had taught himself to make movies, and with financial help from relatives, he became a pioneer of extremely low-budget, independent production. His first two features were the allegorical war picture Fear and Desire (1953) and the noir thriller Killer’s Kiss (1955), on both of which he served not only as producer and director but also as photographer, editor, and sound engineer. Then, in 1955, the preternaturally gifted Kubrick became a low-budget Hollywood director, joining forces with his contemporary the producer James B. Harris to make The Killing, a stylish heist film that was glowingly reviewed and much talked about within the industry but dumped into grind houses by its distributor, United Artists. His second film with Harris, a return to the theme of war, was even more impressive; Paths of Glory (1957), a scathing depiction of the murderous, face-saving machinations of an officer class, secured the young Kubrick’s reputation as a major talent.

The film originated when, on the strength of The Killing, Harris and Kubrick were briefly hired by MGM, where they proposed several projects that were rejected by the studio. Among these was an adaptation of Humphrey Cobb’s 1935 novel Paths of Glory, which Kubrick remembered having read in his father’s library as a teenager. Inspired by a New York Times story about five French soldiers in World War I who were executed by firing squad, the novel provided a harrowing account of trench warfare and an appalling picture of how generals treated their troops as cannon fodder. Playwright Sydney Howard had authored a Broadway adaptation in 1938, but by the mid-1950s, the book was virtually forgotten. Despite Kubrick’s enthusiasm, MGM turned the idea down, chiefly because it feared such a film would have difficulty getting distribution in Europe. Undeterred, Kubrick continued to develop a screenplay, aided by pulp novelist Jim Thompson, who had worked on The Killing, and playwright and novelist Calder Willingham, who had contributed to other unproduced Harris-Kubrick projects at MGM. This document ultimately came to the attention of a powerful and intelligent star: the muscular, dimple-chinned, intensely emotional Kirk Douglas, who was so impressed by it and by Kubrick’s work on The Killing that he offered to take the leading role and to pressure United Artists into financing the film under the auspices of his own company, Bryna Productions. With Douglas’s support, Paths of Glory went before the cameras on locations near Munich, Germany, budgeted at $1 million, more than a third of which went to the star. Harris and Kubrick agreed to work for a percentage of the profits, if profits ever came.

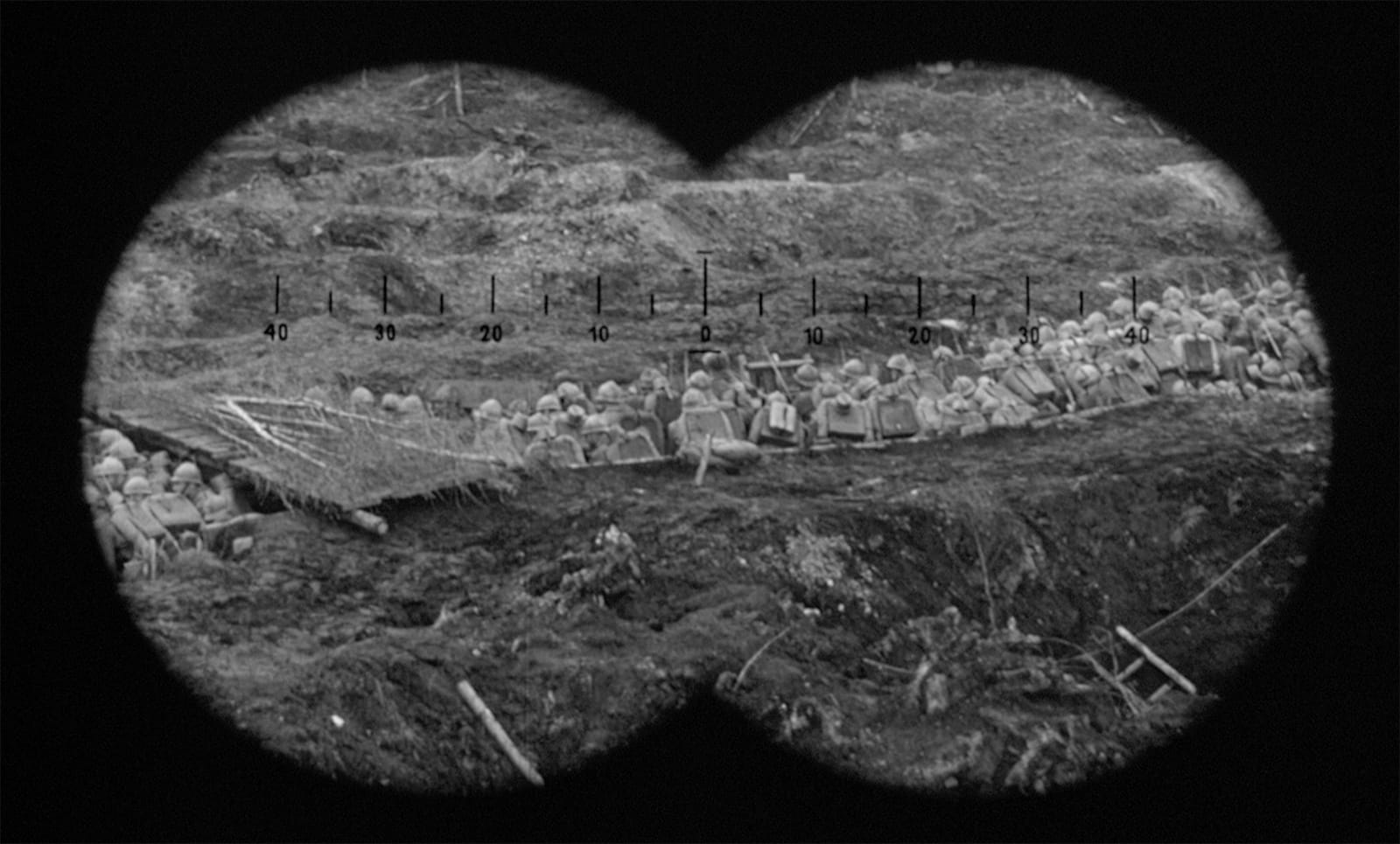

The completed film is strongly marked by what came to be known as Kubrick’s style and favored themes: a mesmerizing deployment of wide-angle tracking shots and long takes, an ability to make a realistic world seem strange, an interest in the grotesque, and a fascination with the underlying irrationality of supposedly rational planning. World War I was a particularly apt subject for Kubrick: generated by a meaningless tangle of nationalist alliances, it resulted in more than eight million military deaths, most caused by benighted politicians and generals who arranged massive bombardments and suicidal charges over open ground. Significantly, the concept of black humor, which is central to Kubrick’s work, was first articulated by the protosurrealist Jacques Vaché, a veteran of trench warfare in World War I, and yet of the several major films about the war, only Paths of Glory depicts the conflict in all its cruel, almost laughably absurd logic (All Quiet on the Western Front, Grand Illusion, The Dawn Patrol, and Sergeant York are humanistic, romantic, or patriotic by comparison). No wonder Luis Buñuel was among its passionate admirers.

To find anything similar to this attitude toward war, we need to consult Kubrick’s other films on the subject. In most cases, he underlines war’s absurdity by making the true conflict internecine and the ostensible enemy either semi-invisible or nearly indistinguishable from the story’s protagonists. In Fear and Desire, the paradigmatic instance, the same actors play both sides in a mysterious battle, as if the film were trying to illustrate a famous line from Walt Kelly’s Pogo: “We have met the enemy and he is us.” On the rare occasions when Kubrick’s soldiers have a close encounter with an Other from behind the lines, that person is either a doppelgänger or a woman. In Paths of Glory, the enemy is almost unseen, consisting mainly of lethal gunfire emanating from the smoke and darkness of no-man’s-land. The film differs from Kubrick’s normal pattern only in that, when French soldiers encounter a female German captive, she’s less an object of perverse desire and anxiety—as in Fear and Desire and Full Metal Jacket (1987)—than a maternal figure, producing a flood of repressed emotion and a momentary dissolution of psychic and bodily armor.